In our previous articles, we explored the Generator and Pipeline patterns, which are ideal for scenarios where a single consumer processes a stream of data. These patterns are powerful, but they can be limited in situations where you want to fully leverage the capabilities of modern multi-core processors or need to handle I/O-bound tasks more efficiently. To achieve this, we can extend our approach to distribute workloads across multiple consumers. This is where the Fan-Out and Fan-In concurrency patterns come into play.

In this article, we’ll dive into these two essential patterns. The Fan-Out pattern allows you to parallelize tasks by distributing work across multiple goroutines, while the Fan-In pattern aggregates the results from these parallel tasks back into a single channel. Together, these patterns enable you to maximize concurrency in your Go applications, improving both performance and scalability.

What Are Fan-Out and Fan-In?

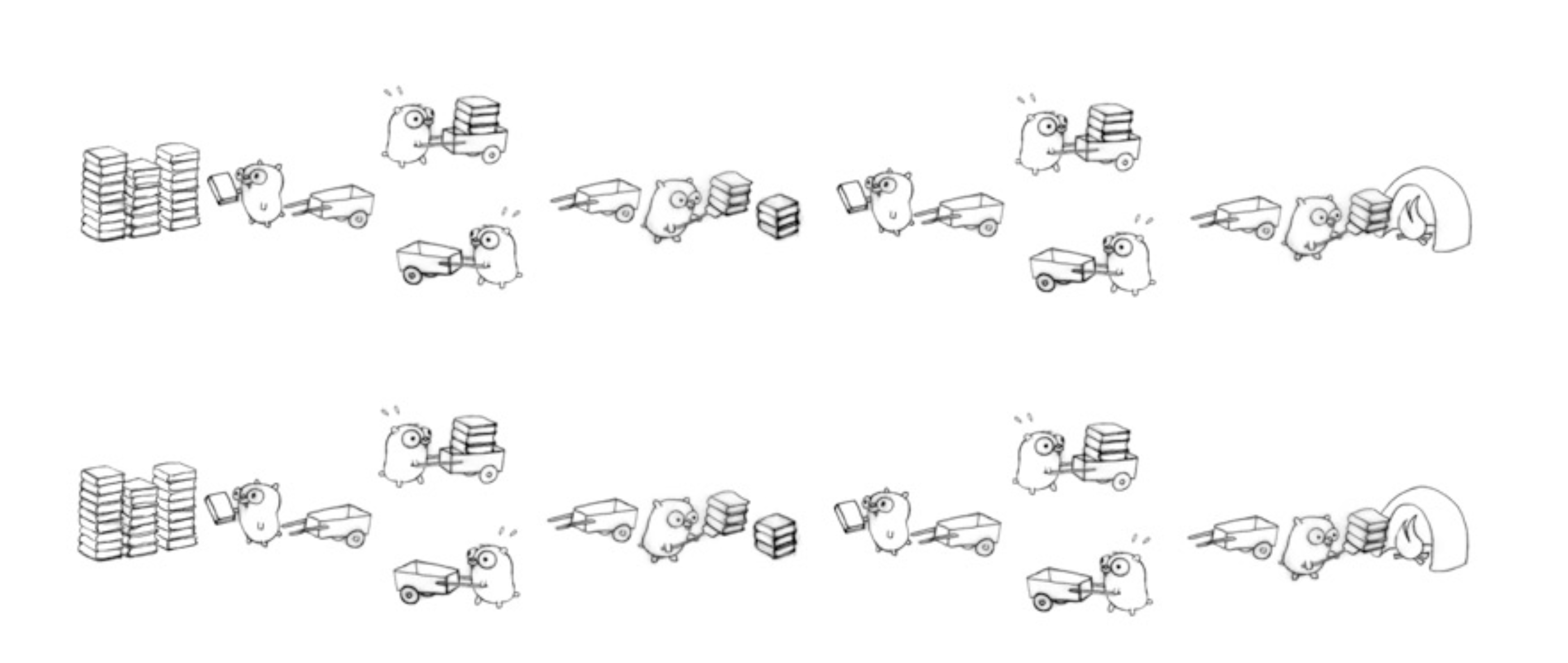

Fan-Out: Distributing Workloads Across Multiple Goroutines

The Fan-Out pattern involves distributing data from a single source (channel) to multiple consumers. Each consumer is a separate goroutine that processes part of the workload. By doing this, you can take advantage of parallelism, where multiple goroutines execute concurrently, thereby reducing the time needed to complete a task.

Imagine you have a task that involves processing a large set of data. Instead of processing each item sequentially, you can distribute the items across multiple workers (goroutines). Each worker handles a portion of the data simultaneously, leading to a significant reduction in overall processing time. This is particularly useful for CPU-bound tasks, where the processing can be done independently across different cores.

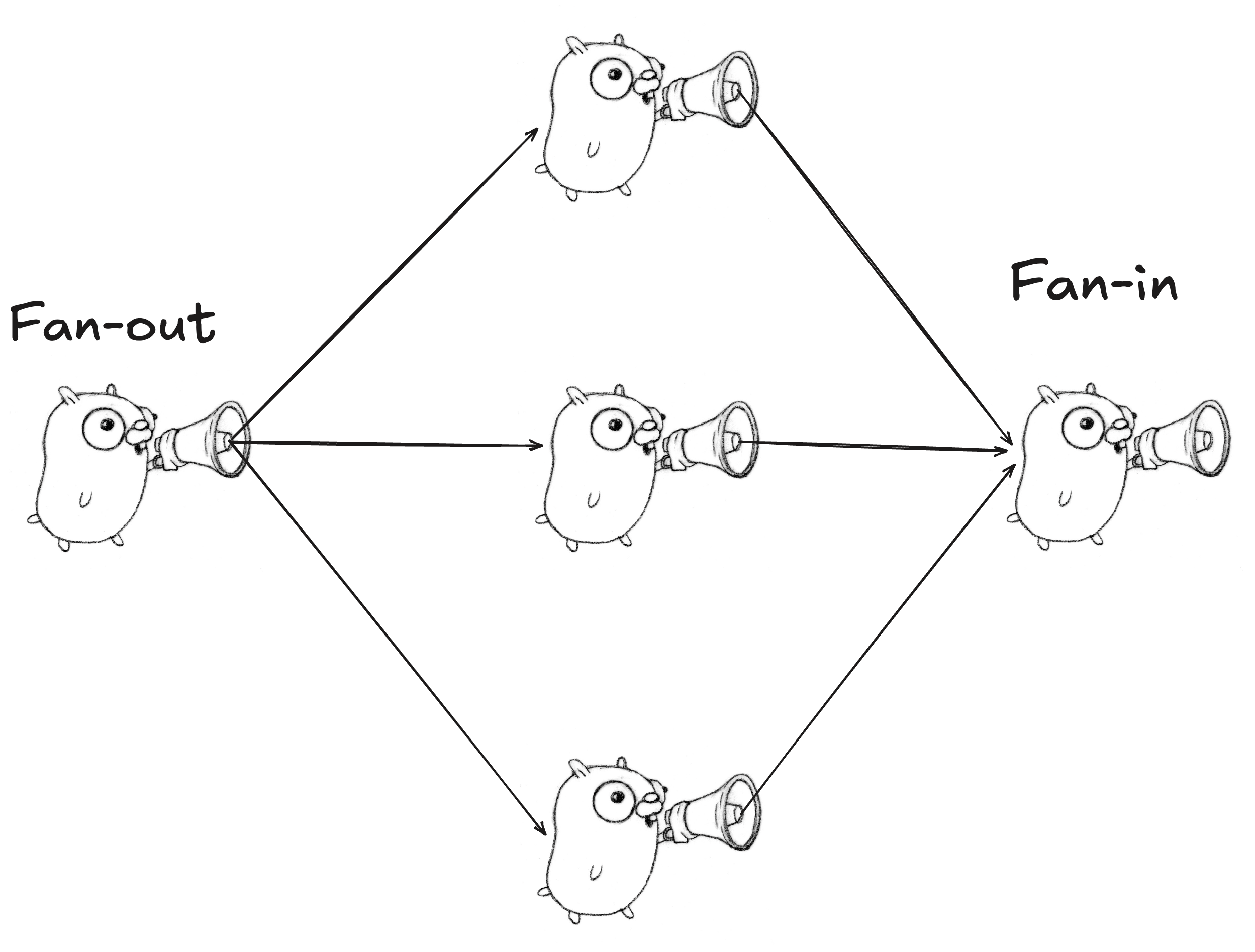

Fan-In: Aggregating Results from Multiple Goroutines

The Fan-In pattern is the complement to Fan-Out. After distributing tasks across multiple goroutines, you need a way to combine the results. Fan-In takes multiple input channels (each corresponding to a consumer) and merges them into a single output channel. This allows you to aggregate the results from parallel processing into one unified stream.

Fan-In is especially useful when you need to gather results from several parallel operations. For instance, if you have multiple goroutines performing calculations or fetching data, you can use Fan-In to collect all the results in a single place for further processing.

To put it simply, Fan-Out distributes the workload among multiple goroutines, and Fan-In aggregates their results back into a single output stream.

Implementing Fan-Out and Fan-In in Go

To illustrate these patterns, let’s start by revisiting the StreamOf function from our previous article on the Pipeline Pattern. This function generates a stream of values that we’ll process using the Fan-Out and Fan-In patterns.

The StreamOf Function

The StreamOf function creates a channel and sends a sequence of values through it. It’s a simple generator that allows us to produce a stream of data for our consumers to process.

func StreamOf[T any](seq ...T) <-chan T {

stream := make(chan T)

go func() {

defer close(stream)

for _, v := range seq {

stream <- v

}

}()

return stream

}

This function takes a variadic list of values of any type and returns a read-only channel that streams these values one by one. The use of a goroutine ensures that the function doesn’t block the caller and allows the values to be consumed concurrently.

Parallel Fibonacci Calculation

Next, let’s define a function to perform a computationally expensive task—calculating Fibonacci numbers. We’ll use this task to demonstrate how Fan-Out can help distribute the workload.

// SlowFibonacci calculates the nth Fibonacci number.

func SlowFibonacci(n int64) int64 {

if n <= 1 {

return n

}

return SlowFibonacci(n-1) + SlowFibonacci(n-2)

}

// fib contains the input number n and the result of the Fibonacci calculation.

type fib struct{ n, result int64 }

// NewFibonacciStream creates a stream of Fibonacci numbers.

func NewFibonacciStream(in <-chan int64) <-chan fib {

out := make(chan fib)

go func() {

defer close(out)

for v := range in {

out <- fib{

n: v,

result: SlowFibonacci(v),

}

}

}()

return out

}

In this code, SlowFibonacci is a recursive function that computes the nth Fibonacci number. It’s deliberately written to be slow, to simulate a CPU-intensive task that benefits from parallelization.

The NewFibonacciStream function creates a new channel that processes input values (Fibonacci indices) from a source channel and outputs the computed Fibonacci numbers. This is the consumer function that we’ll use in our Fan-Out pattern.

Processing Sequentially: A Baseline

Let’s start by running this code sequentially, with a single consumer processing the Fibonacci numbers one by one. This will give us a baseline to compare against the Fan-Out pattern.

func main() {

stream := StreamOf[int64](40, 41, 42, 43, 44)

started := time.Now()

for v := range NewFibonacciStream(stream) {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

fmt.Printf("Elapsed: %v\n", time.Since(started))

// Output:

// {n:40 result:102334155}

// {n:41 result:165580141}

// {n:42 result:267914296}

// {n:43 result:433494437}

// {n:44 result:701408733}

// Elapsed: 5.559868958s

}

In this example, the Fibonacci sequence for each value is calculated one at a time. Since each calculation is slow, the total execution time is around 5.5 seconds. This scenario is ideal for the Fan-Out pattern, which can help reduce the total time by parallelizing the calculations.

Implementing the Fan-Out Pattern

Fan-Out Implementation

Now, let’s see how we can implement the Fan-Out pattern to distribute the workload across multiple goroutines, reducing the total computation time.

func main() {

stream := StreamOf[int64](40, 41, 42, 43, 44)

started := time.Now()

c1 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

c2 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

c3 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(3) // there are 3 consumers.

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for v := range c1 {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

}()

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for v := range c2 {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

}()

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for v := range c3 {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

}()

wg.Wait()

fmt.Printf("Elapsed: %v\n", time.Since(started))

// Output:

// {n:40 result:102334155}

// {n:41 result:165580141}

// {n:42 result:267914296}

// {n:43 result:433494437}

// {n:44 result:701408733}

// Elapsed: 2.94560275s

}

In this example, we create three consumers (c1, c2, and c3), each of which processes the Fibonacci stream concurrently. We use a sync.WaitGroup to ensure the main function waits for all consumers to finish processing before measuring the elapsed time.

By distributing the workload across three goroutines, the total execution time is reduced to around 2.9 seconds, a significant improvement over the sequential approach. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the Fan-Out pattern in parallelizing CPU-bound tasks.

Implementing the Fan-In Pattern

Merging Results with Fan-In

After distributing the work, we need to aggregate the results. The Fan-In pattern helps us collect the output from multiple consumers into a single channel, making it easier to manage and process the results.

func Merge(in ...<-chan fib) <-chan fib {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

out := make(chan fib)

worker := func(ch <-chan fib) {

defer wg.Done()

for v := range ch {

out <- v

}

}

wg.Add(len(in))

for _, stream := range in {

go worker(stream)

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(out)

}()

return out

}

The Merge function takes a variadic number of input channels and returns a single output channel. It uses a sync.WaitGroup to wait for all the input channels to be processed before closing the output channel. This pattern allows you to gather the results from multiple goroutines into one place, making it easier to handle downstream.

Using the Merge Function

Now, let’s see how the Fan-In pattern can be used in conjunction with Fan-Out to process and aggregate results from multiple consumers.

func main() {

stream := StreamOf[int64](40, 41, 42, 43, 44)

started := time.Now()

c1 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

c2 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

c3 := NewFibonacciStream(stream)

for v := range Merge(c1, c2, c3) {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

fmt.Printf("Elapsed: %v\n", time.Since(started))

// Output:

// {n:40 result:102334155}

// {n:41 result:165580141}

// {n:42 result:267914296}

// {n:43 result:433494437}

// {n:44 result:701408733}

// Elapsed: 2.94560275s

}

In this example, the Merge function combines the outputs from three separate consumers (c1, c2, and c3) into a single channel. This allows the results from all three goroutines to be processed together, in the order they complete. By using the Fan-In pattern, we ensure that all the data processed in parallel is collected efficiently and is ready for further processing in a unified manner.

The execution time remains around 2.9 seconds, demonstrating that while the tasks were distributed among multiple goroutines (Fan-Out), the results were seamlessly aggregated back into a single stream (Fan-In). This combination of patterns is powerful in scenarios where both parallel processing and result aggregation are required.

Enhancing the Patterns with Abstraction

While the Fan-Out and Fan-In implementations work well as demonstrated, the code can be made even more reusable and concise. We can abstract the Fan-Out and Fan-In logic into a single function that handles both patterns, allowing for easier scaling and maintenance.

The Distribute Function

To simplify the creation of consumers and the merging of their results, we can use a function that abstracts the Fan-Out and Fan-In patterns. This function will allow us to specify the number of consumers (replicas) and automatically distribute the workload among them.

func Distribute(

source <-chan int64,

task func(source <-chan int64) <-chan fib,

replicas int,

) <-chan fib {

consumers := make([]<-chan fib, replicas)

for i := 0; i < replicas; i++ {

consumers[i] = task(source)

}

return Merge(consumers...)

}

The Distribute function takes three arguments:

source: The input channel providing the data to be processed.task: A function that represents the work each consumer will perform.replicas: The number of consumers (goroutines) to spawn.

The function creates a slice of channels, each corresponding to a consumer, and then uses the Merge function to aggregate their outputs. This pattern simplifies the creation of parallel processing pipelines and reduces boilerplate code.

Using the Distribute Function

Now, let’s see how this abstraction makes the main program more concise and scalable:

func main() {

stream := StreamOf[int64](40, 41, 42, 43, 44)

started := time.Now()

for v := range Distribute(stream, NewFibonacciStream, 5) {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

fmt.Printf("Elapsed: %v\n", time.Since(started))

// Output:

// {n:40 result:102334155}

// {n:41 result:165580141}

// {n:42 result:267914296}

// {n:43 result:433494437}

// {n:44 result:701408733}

// Elapsed: 2.401358083s

}

In this implementation, the Distribute function is used to create five consumers that handle the workload in parallel. The code is much cleaner and more flexible—scaling the number of consumers is as simple as changing the replicas argument.

By using the Distribute function, you’ve combined both Fan-Out and Fan-In into a single, easy-to-use abstraction. This makes your code more maintainable and allows you to scale your processing pipeline effortlessly.

Enhancing the Patterns with Generics

Go’s support for generics, introduced in version 1.18, allows us to make these patterns even more flexible by enabling the processing of different data types without modifying the function signatures.

Generic Distribute and Merge Functions

Here’s how we can refactor the Distribute and Merge functions to use generics:

// Distribute distributes the input stream to multiple workers.

func Distribute[InpStream ~<-chan T, OutStream ~<-chan U, T, U any](

s InpStream,

worker func(s InpStream) OutStream,

replicas int,

) OutStream {

consumers := make([]OutStream, replicas)

for i := 0; i < replicas; i++ {

consumers[i] = worker(s)

}

return Merge(consumers...)

}

// Merge merges multiple streams into a single stream.

func Merge[Stream ~<-chan T, T any](sources ...Stream) Stream {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

out := make(chan T)

worker := func(ch Stream) {

defer wg.Done()

for v := range ch {

out <- v

}

}

wg.Add(len(sources))

for _, stream := range sources {

go worker(stream)

}

go func() {

wg.Wait()

close(out)

}()

return out

}

With these generic functions, Distribute and Merge can now handle any type of input and output streams. The use of type parameters (T and U) makes the code more flexible and reusable across different use cases.

Enhancing the Patterns with Cancellation

Handling cancellation is crucial in long-running operations to ensure that resources are not wasted when a task is no longer needed. Go provides the context package to manage cancellation signals. By incorporating context.Context into our Fan-Out and Fan-In patterns, we can gracefully stop operations when a deadline is reached or when cancellation is requested.

Adding Cancellation Support

Here’s an enhanced version of the Distribute and Merge functions with cancellation support:

diff --git a/fan-out-fan-in/distribute.go b/fan-out-fan-in/distribute.go

index 744d69e..22208b2 100644

--- a/fan-out-fan-in/distribute.go

+++ b/fan-out-fan-in/distribute.go

@@ -1,6 +1,7 @@

package main

import (

+ "context"

"fmt"

"sync"

"time"

@@ -18,36 +19,50 @@ func SlowFibonacci(n int64) int64 {

type fib struct{ n, result int64 }

// NewFibonacciStream creates a stream of Fibonacci numbers.

-func NewFibonacciStream(in <-chan int64) <-chan fib {

+func NewFibonacciStream(ctx context.Context, in <-chan int64) <-chan fib {

out := make(chan fib)

go func() {

defer close(out)

- for v := range in {

- out <- fib{

- n: v,

- result: SlowFibonacci(v),

+ for {

+ select {

+ case <-ctx.Done():

+ return

+ case n, ok := <-in:

+ if !ok {

+ return

+ }

+ out <- fib{n: n, result: SlowFibonacci(n)}

}

}

}()

return out

}

-func StreamOf[T any](seq ...T) <-chan T {

+// StreamOf creates a stream of items of type T.

+func StreamOf[T any](ctx context.Context, seq ...T) <-chan T {

stream := make(chan T)

go func() {

defer close(stream)

- for _, v := range seq {

- stream <- v

+ for _, item := range seq {

+ select {

+ case <-ctx.Done():

+ return

+ case stream <- item:

+ }

+

}

}()

return stream

}

-func Distribute(

- source <-chan int64,

- task func(source <-chan int64) <-chan fib,

+// Distribute distributes the input stream to multiple workers.

+func Distribute[InpStream ~<-chan T, OutStream ~<-chan U, T, U any](

+ ctx context.Context,

+ s InpStream,

+ worker func(ctx context.Context, s InpStream) OutStream,

replicas int,

-) <-chan fib {

- consumers := make([]<-chan fib, replicas)

+) OutStream {

+ consumers := make([]OutStream, replicas)

for i := 0; i < replicas; i++ {

- consumers[i] = task(source)

+ consumers[i] = worker(ctx, s)

}

- return Merge(consumers...)

+ return Merge(ctx, consumers...)

}

-func Merge(in ...<-chan fib) <-chan fib {

+// Merge merges multiple streams into a single stream.

+func Merge[Stream ~<-chan T, T any](ctx context.Context, sources ...Stream) Stream {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

+ out := make(chan T)

- out := make(chan fib)

- worker := func(ch <-chan fib) {

+ worker := func(ch Stream) {

defer wg.Done()

- for v := range ch {

- out <- v

+ for {

+ select {

+ case <-ctx.Done():

+ return

+ case v, ok := <-ch:

+ if !ok {

+ return

+ }

+ out <- v

+ }

}

}

- wg.Add(len(in))

- for _, stream := range in {

+ wg.Add(len(sources))

+ for _, stream := range sources {

go worker(stream)

}

func main() {

ctx, cancel := context.WithTimeout(context.Background(), 2*time.Second)

defer cancel()

stream := StreamOf[int64](ctx, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44)

started := time.Now()

for v := range Distribute(ctx, stream, NewFibonacciStream, 2) {

fmt.Printf("%+v\n", v)

}

fmt.Printf("Elapsed: %v\n", time.Since(started))

// Output:

// {n:40 result:102334155}

// {n:41 result:165580141}

// Elapsed: 2.401358083s

}

In this enhanced version, the context.Context is passed to the Distribute and Merge functions, allowing them to react to cancellation signals. When the context is canceled (e.g., due to a timeout), all workers will stop processing, and the resources will be freed up. This is particularly useful in real-world applications where tasks might need to be aborted if they are no longer relevant.

Now, all workers will automatically cancel when the deadline is exceeded, preventing unnecessary computation and ensuring efficient resource management.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored two important Go concurrency patterns: Fan-Out and Fan-In. These patterns help you distribute work across multiple goroutines and then combine their results into one stream. This approach makes your programs run faster and more efficiently.

We started with the Fan-Out pattern, which spreads tasks across several goroutines, allowing them to run in parallel. Then, we looked at the Fan-In pattern, which collects the results from these parallel tasks into a single channel.

To make these patterns even more powerful, we introduced a Distribute function that combines both Fan-Out and Fan-In. We also used Go’s generics to make the patterns flexible, so they can work with different types of data. Additionally, we added support for cancellation with context.Context, which helps manage resources better and allows tasks to be stopped when they’re no longer needed.

By using these patterns and enhancements, you can build Go programs that are faster, more scalable, and easier to manage. Whether you’re handling multiple tasks at once or processing large amounts of data, these concurrency patterns will be very useful.

You can the full code in this GitHub repository for more insights. Go Concurrency Patterns: Fan-Out and Fan-In

What’s Next?

This article concludes our series on Go Concurrency Patterns. By now, you should have a solid understanding of several key concurrency patterns in Go, including Generators, Pipelines, Fan-Out, and Fan-In. Each pattern serves a unique purpose in handling concurrent operations, and together, they provide a powerful toolkit for building scalable and efficient Go applications.

In future explorations, you might consider diving deeper into more advanced concurrency concepts in Go, such as context management, rate limiting, or error handling in concurrent operations. These topics will further enhance your ability to write robust, production-grade Go applications that can handle complex workloads with ease.

Thank you for following along with this series! Stay tuned for more deep dives into Go and other programming topics.