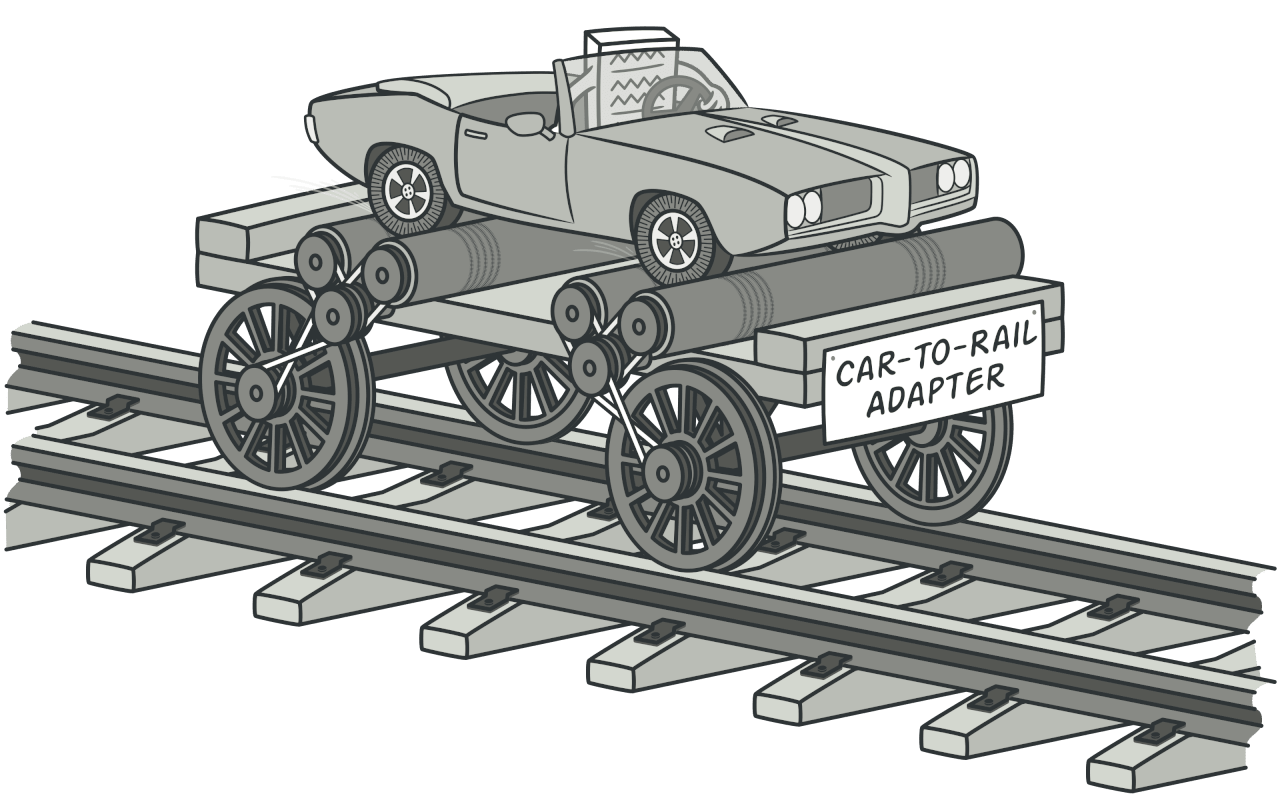

The Adapter Pattern is a structural design pattern that allows objects with incompatible interfaces to collaborate1.

Let me clarify something: an interface does not always mean the type Something interface, but in this context, it is more likely to refer to the contract between types.

ATTENTION: I am not sponsored by Refactoring.Guru, but I definitely recommend that you buy the “DESIGN PATTERNS” book. It covers all known design patterns in depth and provides easy and simple explanations. This post only covers practical examples of each pattern in a real-world Golang application.

In real word application, we will be often we found case where two or more interface is not compatible, but we want it collaborate together to solve our problem. Let me show you an example:

// HealthHandler is a handler for health check.

type HealthHandler struct {}

// NewHealthHandler creates a new health handler.

func NewHealthHandler() *HealthHandler {

return &HealthHandler{}

}

// ServeHTTP implements http.Handler.

func (h *HealthHandler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

started := time.Now()

l := slog.Default().With("method", r.Method, "uri", r.RequestURI)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

if _, err := io.WriteString(w, "OK"); err != nil {

l.Error("could not write response", "error", err)

} else {

l.Info("health check success", "latency", time.Since(started))

}

}

// RegisterRoutes registers all routes to mux.

func RegisterRoutes(mux *http.ServeMux) {

log := slog.New(slog.NewTextHandler(os.Stderr, &slog.HandlerOptions{}))

slog.SetDefault(log)

health := NewHealthHandler(log)

mux.Handle("/api/v1/health", health)

}

The code above is straightforward. We have a simple health check handler registered at the path /api/v1/health, and for the sake of simplicity, we allow all methods. When a request is received by the handler, it logs request information and latency. As we can see, the handler is very simple, but we need to create a new type to satisfy the http.Handler interface.

While the handler is quite simple, we need to create a new type to implement the http.Handler interface. This is because mux.Handle only accepts that interface. You might argue that there is mux.HandlerFunc to simplify this, but for now, let’s pretend it doesn’t exist.

What if we could use a regular function like the one below:

// ServeHTTP handles health check requests.

func ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

started := time.Now()

logger := slog.Default().With("method", r.Method, "uri", r.RequestURI)

w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK)

if _, err := io.WriteString(w, "OK"); err != nil {

logger.Error("could not write response", "error", err)

} else {

logger.Info("health check success", "latency", time.Since(started))

}

}

// RegisterRoutes registers all routes with mux.

func RegisterRoutes(mux *http.ServeMux) {

logger := slog.New(slog.NewTextHandler(os.Stderr, &slog.HandlerOptions{}))

slog.SetDefault(logger)

mux.Handle("/api/v1/health", ServeHTTP)

}

However, this approach will not work; it will result in a compilation error because http.Handler is not compatible with func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request), which is the type of ServeHTTP. Even though http.Handler.ServeHTTP has the same function signature as ServeHTTP, what makes them incompatible?

In an interface type, the name is considered part of the contract. In the http.Handler, it expects the implementation to have a method with the exact signature: ServeHTTP(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request). On the other hand, ServeHTTP is just an ordinary function. In a function, the function name is not included as part of the type contract. So, they are not compatible because one is a method, and the other is a function.

Now it is clear that the function signatures match. The only problem is how to transform that regular or ordinary function into a method with the name that http.Handler expects.

This is where the Adapter Pattern comes in.

In the Adapter Pattern, there are typically three main components:

- Target: This is the type that the client expects. In our case, the client is

mux.Handle, which expectshttp.Handleras the second argument. - Adaptee: This is a type that needs to be adapted to work with the target type. In our case, the adaptee is the regular function

ServeHTTP. - Adapter: This is a type that bridges the gap between the target and the adaptee. This type must be compatible with both the target and the adaptee. The Adapter translates calls from the Target interface into calls to the Adaptee’s interface.

We already have both the target and the adaptee; the only missing part is the adapter.

Fortunately, in Go, a function is a first-class citizen, meaning we can treat functions like any other values, including defining methods on function types. Since the function name is not included as part of the contract, we can define a new type with the signature func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request), and automatically any function that matches the argument and return types will be compatible with this new type. This new type will be compatible with the Adaptee. Let’s see this in action.

type Adapter func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request)

// check if the Adapter is compatible with the regular function ServeHTTP. If it's not compatible, it will not compile.

var _ Adapter = ServeHTTP

Now we need to make the Adapter type compatible with the target, which is the http.Handler. Since the adapter is a type, we can define a method to implement the http.Handler interface. Let’s see this in action:

type Adapter func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request)

// check if the Adapter is compatible with the regular function ServeHTTP. If it's not compatible, it will not compile.

var _ Adapter = ServeHTTP

// check if the Adapter is compatible with the http.Handler.

var _ http.Handler = Adapter(nil)

// ServeHTTP implements the http.Handler.

func (a Adapter) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

panic("unimplemented")

}

Now, the Adapter type is compatible with both the target and the adaptee. However, when the target is called, the adaptee is not called yet.

Since we’ve made the regular function ServeHTTP a type of Adapter, the a in (a Adapter) receiver is the adaptee.

So, to delegate the call to the adaptee, we simply call a with w and r as the arguments. Let’s see the full example:

type Adapter func(http.ResponseWriter, *http.Request)

// check if the Adapter is compatible with the regular function ServeHTTP. If it's not compatible, it will not compile.

var _ Adapter = ServeHTTP

// check if the Adapter is compatible with the http.Handler.

var _ http.Handler = Adapter(nil)

// ServeHTTP implements the http.Handler.

func (a Adapter) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

// delegates the call to the adaptee.

a(w, r)

}

// RegisterRoutes registers all routes with mux.

func RegisterRoutes(mux *http.ServeMux) {

logger := slog.New(slog.NewTextHandler(os.Stderr, &slog.HandlerOptions{}))

slog.SetDefault(logger)

// cast the regular ServeHTTP function to Adapter type.

adapter := Adapter(ServeHTTP)

mux.Handle("/api/v1/health", adapter)

}

Now, this code will compile; the magic happens in this code: Adapter(ServeHTTP). What we’re doing here is the same as what http.HandlerFunc and mux.HandleFunc do. Let’s take a look at what the documentation says:

// The HandlerFunc type is an adapter to allow the use of

// ordinary functions as HTTP handlers. If f is a function

// with the appropriate signature, HandlerFunc(f) is a

// Handler that calls f.

type HandlerFunc func(ResponseWriter, *Request)

// ServeHTTP calls f(w, r).

func (f HandlerFunc) ServeHTTP(w ResponseWriter, r *Request) {

f(w, r)

}

// HandleFunc registers the handler function for the given pattern.

func (mux *ServeMux) HandleFunc(pattern string, handler func(ResponseWriter, *Request)) {

if handler == nil {

panic("http: nil handler")

}

mux.Handle(pattern, HandlerFunc(handler))

}

Actually, you don’t need to create your own adapter. The net/http package has already created one for us. However, understanding how this concept works is still important.

Since we are working with functions here, as opposed to objects in object-oriented programming (OOP) languages, we make a function compatible with an interface and define an Adapter that is also a function type. I would like to call this a “Functional Adapter” to differentiate it from OOP-like adapters, as demonstrated by Refactoring.Guru in their example.

This pattern is very useful, especially for mocking in unit tests. We can find this pattern in Go’s source code itself. Let me provide a few examples in the list below:

In these examples, the common factor is that the target interfaces have only one method. While it’s not limited to just one method, using a Functional Adapter is typically the best approach when there’s only one method.

So how about the OOP-like Adapter pattern?

Besides using the OOP-like Adapter or Functional Adapter, the concept remains the same. You need to define the three main components: Target, Adaptee, and the Adapter.

Is there any example in the Go standard library that uses the OOP-like Adapter Pattern?

Yes, the database/sql driver. In this context, the three main components will be as follows:

- The Target:

sql.DBfromdatabase/sql. - The Adaptee: the specific database implementation, such as MySQL, PostgreSQL, etc. Please note that the Adaptee is not the driver like github.com/lib/pq, but the actual implementation that communicates with the database. This might have a completely different set of methods compared to

sql.DB. - The Adapter is the database driver like github.com/lib/pq.

I believe that covers everything for now. I hope you have enjoyed this article. If you have any questions or suggestions, please don’t hesitate to leave a comment below. Thank you for reading!